Imagine a shield protecting our planet, deflecting cosmic rays and solar winds that would otherwise strip away our atmosphere and render life impossible. This invisible guardian isn't some futuristic technology; it's a magnetic field generated by the violent, churning heart of our world. Deep beneath your feet, where pressures are immense and temperatures mimic the surface of the sun, lies a crucial layer: The Outer Core: Composition, State, and Conditions. This dynamic realm is the ultimate engine for Earth's life-sustaining magnetosphere, a place of extreme physics and chemistry that shapes our very existence.

Understanding the outer core isn't just for geophysicists; it's about appreciating the intricate dance of forces that make Earth a truly unique and habitable world. Let's peel back the layers and discover the secrets held within this molten engine.

At a Glance: Earth's Outer Core

- Location: Below the mantle, surrounding the solid inner core.

- Depth: Starts around 2,889-2,890 km (1,795 miles) below the surface, extending to 5,150 km (3,200 miles).

- Thickness: Approximately 2,260 km (1,400 miles).

- State: Liquid (molten metal). Confirmed because seismic shear waves (S-waves) cannot pass through it.

- Composition: Primarily a molten iron-nickel alloy (85-88% iron, 5-10% nickel) mixed with lighter elements like sulfur, oxygen, silicon, and hydrogen.

- Temperature: Ranges from 4,000-4,400°C near the mantle to 6,000-6,100°C near the inner core.

- Pressure: Increases from 135 Gigapascals (GPa) to 330 GPa.

- Key Role: Generates Earth's magnetic field through vigorous convection of electrically conductive liquid metal.

What is the Outer Core, Anyway? A Deep Dive into Earth's Inner Landscape

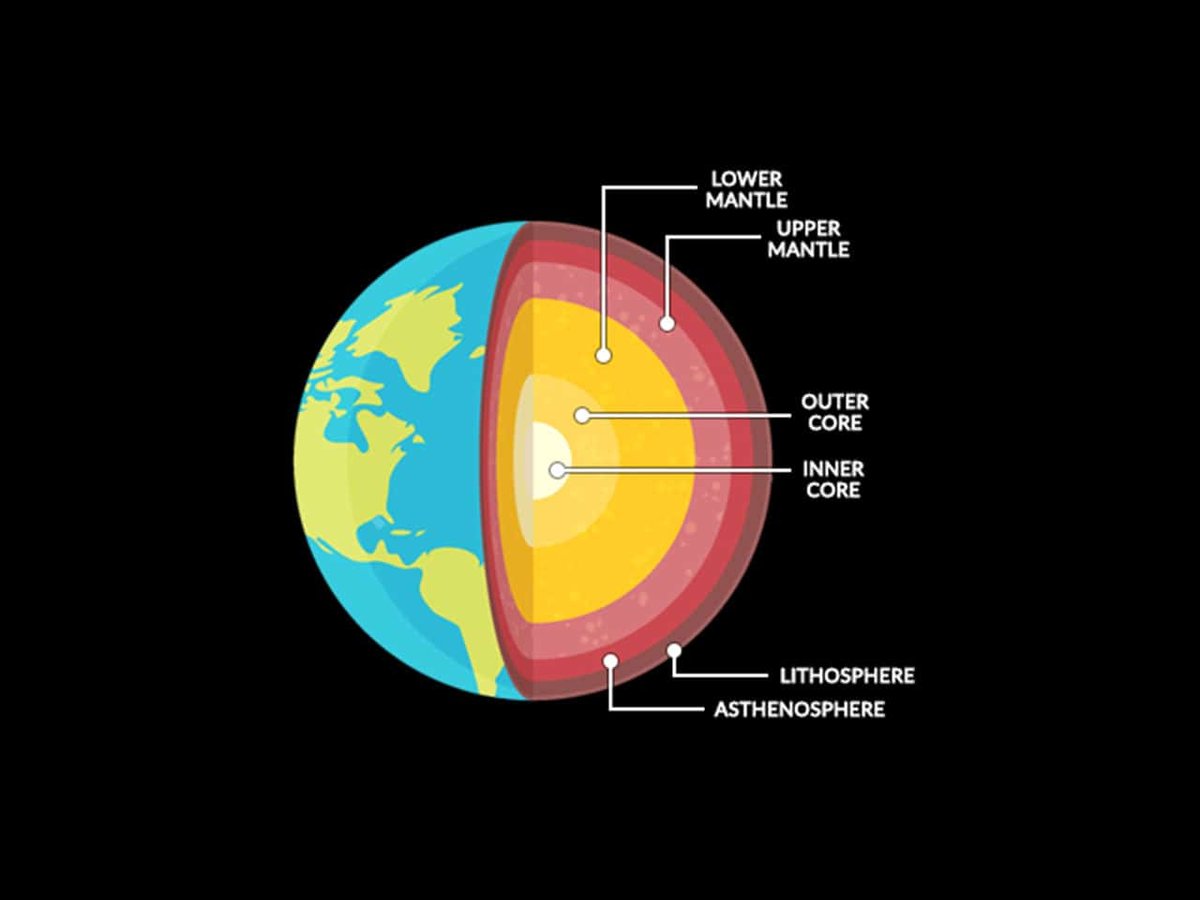

To truly grasp the significance of the outer core, you first need a mental map of our planet's hidden depths. Picture Earth not as a solid ball, but as an onion with distinct, nested layers. The outer core is the second-to-last of these layers, nestled between the rocky mantle above it and the solid inner core at the very center.

This colossal layer begins an astonishing 2,889 to 2,890 kilometers (about 1,795 miles) beneath the surface, far deeper than any human has ever drilled. It stretches down to a depth of about 5,150 kilometers (3,200 miles), giving it an impressive thickness of roughly 2,260 kilometers (1,400 miles). To put that into perspective, the outer core alone is thicker than the entire Earth's crust and mantle combined!

What truly sets the outer core apart is its unique physical state: it's entirely liquid. This isn't just any liquid, though. We're talking about a sea of superheated, molten metal, flowing with an astounding, albeit slow, dynamism. This liquid state is no mere guess; seismology—the study of earthquake waves—provides direct evidence. Seismic shear waves (S-waves), which travel through solids, cannot propagate through the outer core, confirming its liquid nature.

The Outer Core's Fiery Recipe: A Metallic Stew

Understanding the outer core's composition is key to unlocking its secrets. It's not just a generic "molten rock" but a very specific, electrically conductive metallic alloy that makes the geodynamo possible.

The Iron-Nickel Heart

The primary ingredients in this deep-earth stew are iron and nickel. Scientists estimate the outer core is composed of 85-88% iron and 5-10% nickel. This iron-nickel alloy is incredibly dense, but not as dense as pure iron-nickel would be under such extreme pressures. This slight density deficit tells us something crucial: there must be other, lighter elements mixed in.

The Role of Lighter Elements

These "lighter elements" are thought to include sulfur, oxygen, silicon, and even hydrogen. While they might seem like minor components, their presence is absolutely vital. Why? Because these lighter elements act like a cosmic antifreeze. They lower the melting point of the iron-nickel alloy, allowing it to remain in a liquid state despite the immense pressures and temperatures. Without them, the outer core might solidify, grinding Earth's magnetic engine to a halt.

Beyond lowering the melting point, these lighter elements also play a critical role in driving the powerful convection currents that power the geodynamo. As the inner core grows and freezes, it forces these lighter elements out into the surrounding liquid outer core. This creates compositional differences – less dense, lighter-element-rich fluid rises, while denser, iron-rich fluid sinks – further fueling the outer core's turbulent motion.

A River of Metal: The Outer Core's Liquid State Explained

How can something so deep inside Earth, under unimaginable pressure, remain liquid? It boils down to a delicate balance between temperature and pressure.

The Heat is On: Extreme Temperatures

The outer core is incredibly hot. Temperatures within this layer range from approximately 4,000-4,400°C (7,200-7,950°F) near its boundary with the mantle. As you move deeper, closer to the inner core, the temperatures soar even higher, reaching an astonishing 6,000-6,100°C (10,800-11,000°F). That's comparable to the surface temperature of the sun! This extreme heat energy is largely residual from Earth's formation, supplemented by the release of latent heat as the inner core slowly freezes and the decay of radioactive isotopes in the mantle.

The Squeeze: Immense Pressure

Despite these searing temperatures, the pressure is equally immense. At the outer core's upper boundary, pressure is around 135 Gigapascals (GPa) – that's roughly 1.35 million times atmospheric pressure. By the time you reach the inner core boundary, it can hit an astounding 330 GPa (3.3 million times atmospheric pressure).

So, why liquid? It's all about the interplay. While pressure generally encourages solidification, the outer core's temperature is simply too high for the iron-nickel alloy to crystallize, even under these crushing pressures. For now, the heat wins the battle, maintaining a state of superheated, low-viscosity liquid metal.

Seismic Evidence: The Smoking Gun

Our understanding of the outer core's liquid state isn't just theoretical. It's directly supported by seismology. When an earthquake occurs, it generates different types of seismic waves. P-waves (compressional waves) can travel through solids and liquids. However, S-waves (shear waves), which move by shaking material perpendicular to their direction of travel, cannot pass through liquids. The observed absence of S-waves travelling directly through the outer core is the strongest evidence we have that this vast layer is indeed molten.

The Engine Room: Convection Currents and the Coriolis Effect

The outer core isn't a static pool of molten metal. It's a hyperactive, turbulent engine, constantly in motion. These vigorous movements are what ultimately power Earth's magnetic field.

Thermal and Compositional Gradients: The Driving Forces

Two primary forces drive this relentless churning:

- Thermal Convection: Like water boiling in a pot, hotter, less dense fluid tends to rise, while cooler, denser fluid sinks. In the outer core, heat flows outward from the hotter inner core towards the cooler mantle. This temperature gradient creates density differences, initiating large-scale thermal convection.

- Compositional Convection: This is where those "lighter elements" come into play again. As the solid inner core slowly grows, it crystallizes pure iron and nickel from the surrounding liquid. This process effectively "squeezes out" the lighter elements, enriching the liquid outer core near the inner core boundary with these less dense components. This buoyant, lighter fluid then rises, driving compositional convection currents that are even more powerful than thermal ones.

These combined thermal and compositional gradients create a complex, dynamic system of rising and sinking plumes of molten metal, constantly mixing and circulating.

Earth's Rotation: The Coriolis Twist

If the Earth weren't spinning, these convection currents might be more chaotic and less organized. However, our planet's rotation, through what's known as the Coriolis effect, plays a critical role in shaping these flows.

The Coriolis effect is an inertial force that acts on moving objects within a rotating reference frame. In the case of the outer core, it deflects the massive, turbulent convection currents, organizing them into structured, spiraling columns. Imagine giant, swirling eddies of molten iron and nickel, twisting and turning as they rise and fall. These organized, helical flows are essential for setting up the conditions necessary to generate a magnetic field.

The Geodynamo: How the Outer Core Generates Earth's Magnetic Field

Now we get to the core (pun intended) of why the outer core is so vital: it's the engine of the geodynamo, the source of Earths magnetic field. Without this incredible mechanism, life as we know it simply wouldn't exist.

Electromagnetic Induction: The Heart of the Process

The geodynamo operates on principles of electromagnetism, specifically a process called electromagnetic induction. Here's the simplified breakdown:

- Electrically Conductive Fluid: The molten iron-nickel alloy of the outer core isn't just liquid; it's also an excellent electrical conductor. Think of it like a giant, liquid wire.

- Moving Convection Currents: The vigorous, spiraling convection currents we just discussed act like massive, moving electrical conductors.

- Generating Electrical Currents: As these conductive fluids move through pre-existing (however small) magnetic fields, they induce electrical currents within themselves, much like a dynamo or generator.

- Amplifying the Field: These newly generated electrical currents, in turn, create their own magnetic fields. This process becomes self-sustaining and self-amplifying. The generated magnetic fields reinforce and strengthen the original field, creating a feedback loop that sustains Earth's magnetic field over geological timescales.

It's an incredibly complex, chaotic, yet ultimately stable system, constantly regenerating and evolving. The energy released by the cooling and crystallization of the inner core provides the continuous push needed to keep this enormous dynamo running.

Our Planetary Shield: Why Earth's Magnetism Matters for Life

The product of the outer core's furious activity—Earth's magnetic field—is more than just a scientific curiosity. It's an indispensable shield that directly impacts our planet's habitability.

Deflecting Harmful Solar Wind and Cosmic Radiation

The sun constantly emits a stream of charged particles called the solar wind, along with much higher-energy cosmic radiation from deep space. Both are incredibly dangerous, capable of damaging DNA, stripping away atmospheres, and making surfaces uninhabitable.

Earth's magnetic field creates a vast protective bubble around our planet, known as the magnetosphere. This magnetosphere acts like a giant force field, deflecting the vast majority of these harmful particles. They are either redirected around the planet or funneled towards the poles, where they interact with the atmosphere to create the stunning auroras.

Protecting Our Atmosphere

Without this magnetic protection, the solar wind would gradually, but relentlessly, strip away Earth's atmosphere. Think of Mars: it once had a thicker atmosphere and perhaps liquid water, but lacking a strong, enduring magnetic field, its atmosphere was largely eroded by the solar wind over billions of years, leaving it the desolate planet we see today. Earth's magnetosphere ensures our atmosphere, and thus our oceans and breathable air, remain intact.

Impact on Navigation and Animal Migration

Beyond its role in habitability, the magnetic field has practical implications for life on Earth. Many animals, from birds to sea turtles, use Earth's magnetic field for navigation during their epic migrations. And, of course, humans have long relied on compasses for direction-finding, a technology directly enabled by the global magnetic field.

Where Worlds Meet: Boundaries of the Outer Core

The outer core doesn't exist in isolation; it constantly interacts with the layers above and below it, creating dynamic boundary zones that influence the entire planet.

The Lehmann Discontinuity: Outer Core to Inner Core

The transition from the liquid outer core to the solid inner core occurs at approximately 5,150 kilometers (3,200 miles) depth and is known as the Lehmann discontinuity. Here, despite the even higher temperatures, the pressure becomes so extreme (up to 330 GPa) that it finally overrides the thermal energy, forcing the iron-nickel alloy to crystallize and solidify.

This isn't a static boundary. The inner core is slowly growing, freezing more of the outer core material onto its surface. This freezing process is critical for the geodynamo, as it releases significant latent heat and forces those lighter elements back into the liquid outer core, as discussed earlier. This process continuously supplies energy and compositional buoyancy to drive the convection currents.

The Core-Mantle Boundary (CMB): A Zone of Intense Interaction

The Core-Mantle Boundary (CMB), located at roughly 2,890 kilometers (1,795 miles) depth, is perhaps one of the most enigmatic and dynamic interfaces within Earth. It's a sharp transition zone where the liquid outer core meets the solid, but ductile, silicate mantle.

This boundary is a place of incredible heat exchange and chemical reactions. The outer core transfers heat to the mantle, driving mantle plumes that can eventually reach the surface, leading to hotspots and volcanic activity.

Scientists have also identified peculiar features at the CMB called Ultra-low Velocity Zones (ULVZs). These are localized regions where seismic waves slow down significantly, suggesting the presence of partially melted rock or chemically distinct material that is denser than the surrounding mantle. These ULVZs are thought to be ancient remnants of subducted oceanic crust or deep mantle plumes, potentially playing a role in how the mantle and core interact. The dynamics at the CMB directly influence both mantle convection and the flow patterns within the outer core, making it a critical area of ongoing research.

A Field in Flux: Variations in Earth's Magnetism

While Earth's magnetic field is a stable, long-lasting shield, it's far from constant. It experiences continuous variations in strength and direction, reminding us that the geodynamo is a dynamic, living system.

Over geological timescales, the magnetic poles wander significantly, sometimes shifting by tens of kilometers per year. More dramatically, the magnetic field occasionally undergoes complete reversals, where the North and South magnetic poles swap places. These reversals are not instantaneous; they occur over hundreds of thousands to millions of years, during which the field's strength temporarily diminishes, potentially exposing Earth to increased radiation.

Studying these past variations, recorded in ancient rocks, provides invaluable clues about the long-term behavior of the outer core and the geodynamo.

Peering into the Depths: How We Study the Outer Core

Since we can't directly sample the outer core, our understanding comes from an ingenious combination of indirect methods.

Seismic Tomography: Earth's X-Ray Vision

Much like medical CT scans use X-rays to image the human body, seismic tomography uses earthquake waves to create 3D images of Earth's interior. By analyzing how seismic waves travel through the planet – how they speed up, slow down, or are deflected – scientists can infer the density, temperature, and physical state of different layers, including the outer core. This is how we confirmed its liquid nature and mapped its boundaries.

Computational Modeling: Simulating the Dynamo

Thanks to supercomputers, scientists can create complex mathematical models that simulate the conditions and processes within the outer core. These computational models incorporate known physics, fluid dynamics, and electromagnetism to replicate the geodynamo. While incredibly challenging, these simulations help us understand how convection currents interact with Earth's rotation to generate and sustain the magnetic field, providing insights into its strength variations and pole reversals.

Extreme Pressure/Temperature Experiments: Recreating the Core

In laboratories, scientists use specialized equipment like diamond anvil cells to recreate the extreme pressures and temperatures found deep within Earth. By squeezing and heating tiny samples of iron, nickel, and proposed lighter elements, they can study how these materials behave under core-like conditions, including their melting points, electrical conductivity, and density. These experiments provide crucial data to refine our understanding of the outer core's composition and state.

The Ticking Clock: The Outer Core's Role in Earth's Habitability

It's impossible to overstate the outer core's importance for Earth's habitability. It's not just a nice-to-have feature; it's a fundamental requirement for complex life.

If, for some reason, the outer core were to solidify—perhaps due to a significant loss of internal heat—the geodynamo would cease. The convection currents would grind to a halt, the electrical currents would dissipate, and Earth's protective magnetic field would collapse.

The consequences would be catastrophic. Our planet would lose its primary shield against the solar wind and cosmic radiation. Over time, the solar wind would gradually strip away our atmosphere, leading to the loss of liquid water on the surface and making the planet exposed and uninhabitable, much like Mars. Earth would transform from a vibrant, blue-green oasis into a barren, red wasteland.

Fortunately, current scientific understanding suggests the outer core is likely to remain liquid and active for billions of years to come, but its long-term stability is a powerful reminder of its critical role.

Unanswered Questions and Future Frontiers

Despite incredible advancements, the outer core still holds many mysteries. Scientists are continually working to refine our understanding of this enigmatic layer.

Future research aims to:

- Improve Geodynamo Models: Develop more sophisticated computational models to better predict the behavior of the magnetic field, including the precise timing and mechanisms of pole reversals.

- Refine Core Composition: Better constrain the exact proportion and identity of the lighter elements within the outer core, as this significantly impacts its density and flow dynamics.

- Unravel Core-Mantle Interactions: Gain a clearer picture of the complex heat and chemical exchange at the CMB, including the nature and origin of ULVZs, and how these interactions influence processes in both the mantle and the core.

- Advance Seismic Techniques: Utilize new seismic data and analysis methods to image the outer core with even greater detail, potentially revealing more about its internal structure and flow patterns.

The Deep Impact: What the Outer Core Means for You

You might never directly interact with the outer core, but its influence pervades every aspect of your life on Earth. It's the silent protector, working tirelessly beneath our feet to ensure our planet remains a haven for life.

Next time you look up at the stars, or even just consider the simple act of breathing, remember the incredible forces at play within Earth's outer core. It's a testament to the dynamic and interconnected nature of our planet, a powerful reminder that even the deepest, most inaccessible parts of Earth are intimately linked to the vibrant life on its surface. Continue to stay curious about our planet's hidden depths; there's always more to learn about the intricate systems that make our world so special.