The Earth isn't just a big rock spinning through space; it's a dynamic, living system, and a huge part of what makes it habitable is something we can't see but interact with constantly: its magnetic field. Understanding the characteristics and significance of Earth's magnetic field is crucial to grasping how our planet functions, protects life, and even guides some of its smallest creatures. This isn't just a scientific curiosity; it's the invisible shield that shapes our very existence.

At a Glance: Earth's Invisible Shield

- What it is: A vast magnetic field extending from Earth's core into space.

- How it's made: Generated by the churning, molten iron and nickel in Earth's outer core—a process called the "geodynamo."

- Its strength: Varies from 22 to 67 microteslas (μT) at the surface, but a powerful 25 gauss in the outer core.

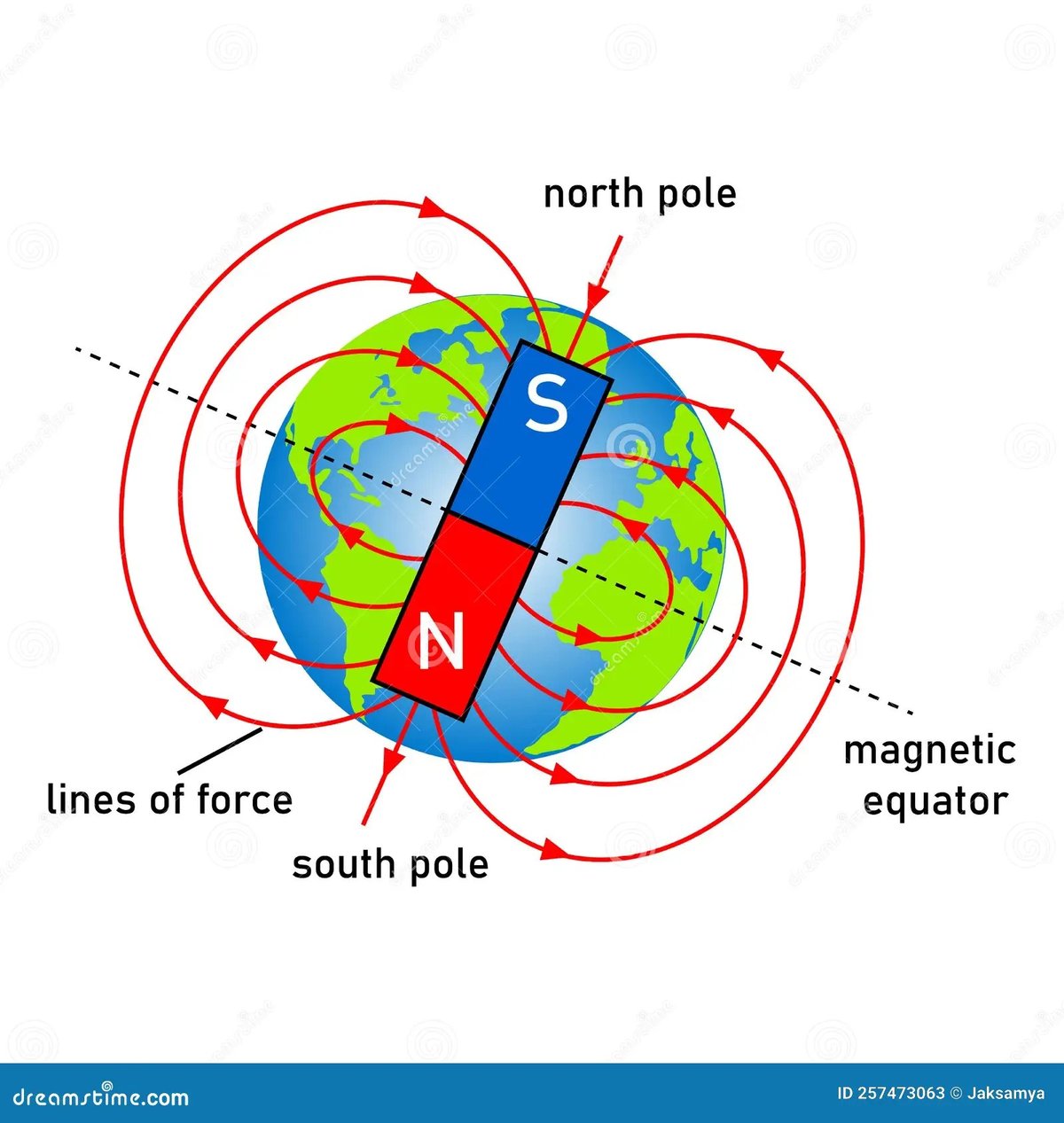

- Its poles: Like a bar magnet, but with its "north" geomagnetic pole actually acting as a magnetic South pole, and vice-versa.

- Its dynamics: It's always moving, shifting, and even occasionally flipping its poles entirely.

- Its superpower: Creates the magnetosphere, protecting Earth from the Sun's harmful radiation and cosmic rays.

- Why it matters: Essential for life, navigation, protecting technology, and even guiding animal migrations.

The Planet's Beating Heart: Where the Magnetic Field Originates

Imagine our Earth as a giant, incredibly complex machine. Deep within its core, beneath thousands of kilometers of rock and mantle, lies a crucial engine. This engine is our planet's outer core—a swirling, superheated ocean of molten iron and nickel. It's here, approximately 2,900 kilometers (1,800 miles) beneath your feet, that the Earth's magnetic field is born.

This isn't a static process. Think of it more like a massive, constantly churning convection oven. Heat escapes from the Earth's even hotter inner core, driving powerful currents within the liquid metal of the outer core. As this electrically conductive fluid moves, it generates electric currents. These currents, in turn, produce a magnetic field. This self-sustaining process is known as the geodynamo. It’s a bit like a bicycle dynamo, but on a planetary scale. This incredible internal engine is where the magnetic field originates, making it one of the most fundamental characteristics of our planet. Without this molten heart, Earth would be a very different, and likely uninhabitable, place.

Unpacking the Characteristics: What the Geomagnetic Field Looks Like

While we can't physically see the magnetic field, scientists have meticulously measured and mapped its characteristics, revealing its intricate structure and dynamic behavior.

Magnitude and Shape: More Than Just a Bar Magnet

At the Earth's surface, the strength of the magnetic field, known as its intensity, varies quite a bit. It typically ranges from about 22 microteslas (μT) near the equator to 67 μT closer to the poles. For context, that's roughly equivalent to 0.22 to 0.67 gauss (G)—a unit you might be more familiar with from magnets you've encountered. Yet, this surface strength is a mere whisper compared to the immense power within the outer core, where the field averages a staggering 25 gauss—50 times stronger!

Often, we visualize Earth's magnetic field as a simple bar magnet, a magnetic dipole, tilted slightly within the planet. This approximation is useful, and indeed, the field is tilted about 11 degrees relative to Earth's rotational axis. However, this is a simplification. The real field is far more complex, with smaller, non-dipole components that cause local variations and anomalies.

The Peculiar Case of the Magnetic Poles

One of the most fascinating characteristics is the orientation of the magnetic poles. Here's a mind-bender:

- The North geomagnetic pole, currently located near Ellesmere Island in Nunavut, Canada, is actually the South pole of Earth's internal magnetic field.

- Conversely, the South geomagnetic pole corresponds to the North pole of Earth's magnetic field.

Why the switch? It's a convention rooted in the fact that the "north-seeking" end of a compass needle points towards the North geomagnetic pole. For that to happen, the geomagnetic pole itself must possess the opposite magnetic polarity (like how opposite ends of a magnet attract).

Field intensity tends to be strongest near these poles and weakest around the magnetic equator. One notable exception is the South Atlantic Anomaly, an area over South America and the southern Atlantic Ocean where the magnetic field is significantly weaker. This dip allows charged particles from space to dive closer to the Earth's surface, posing risks to satellites and spacecraft as they pass through. Maxima, on the other hand, are observed over northern Canada, Siberia, and parts of the Antarctic coast.

Defining the Field: The Three Vector Components

To precisely describe Earth's magnetic field at any given point, scientists use three key vector components:

- Declination (D): This is the horizontal angle between magnetic North (where your compass points) and true North (the geographic North Pole). Declination varies depending on your location, which is why maps often include local declination values for navigation.

- Inclination (I) or Magnetic Dip: Imagine a compass needle that's free to pivot vertically. This is the angle the magnetic field lines make with the horizontal surface of the Earth.

- At the North Magnetic Pole, the inclination is 90° downwards (the field points straight down).

- At the magnetic equator, it's 0° (the field is perfectly horizontal).

- At the South Magnetic Pole, it's –90° upwards (the field points straight up).

Magnetic dip is a critical indicator of proximity to the magnetic poles.

- Intensity (F): As mentioned, this is the total strength of the magnetic field at that location, typically measured in microteslas (μT) or nanoteslas (nT), or sometimes in gauss (G).

These three components provide a complete picture of the magnetic field's direction and strength at any point on the globe.

A Wiggling, Wandering, and Sometimes Flipping Field: Earth's Magnetic Dynamics

The Earth's magnetic field is anything but static. It's a dynamic entity, constantly changing on timescales ranging from minutes to millions of years. These changes are crucial for understanding its long-term stability and its role in Earth's history.

The Moving Poles: A Slow but Steady Drift

If you've ever used a compass, you know magnetic North isn't exactly the same as true North. What you might not realize is that magnetic North is always on the move. Historically, the North Magnetic Pole has been migrating northwestward, but in recent decades, its pace has accelerated significantly, reaching rates of 50–60 kilometers (30–37 miles) per year. It's currently drifting from northern Canada towards Siberia, a journey that has practical implications for navigation systems and mapmakers. This secular variation describes these longer-term changes over years to centuries.

The dipole strength itself has been on a decline, decreasing by about 6.3% per century since 1 AD, with this acceleration noted since the year 2000. While this sounds dramatic, it's within the historical normal ranges of the field's variability. Researchers have found evidence of even faster directional changes in Earth's history, reaching around 10° per year, significantly more rapid than what we observe today.

The Big Flip: Geomagnetic Reversals and Excursions

Perhaps the most dramatic change the geomagnetic field undergoes is a complete reversal, where the North and South Magnetic Poles effectively switch places. These events are irregular, averaging several hundred thousand years between flips. The most recent full reversal, known as the Brunhes–Matuyama reversal, happened about 780,000 years ago. During a reversal, the field doesn't just instantly flip; it weakens significantly, becomes highly unstable, and can have multiple poles for a period before re-establishing itself with reversed polarity. The entire process can take thousands of years.

Then there are geomagnetic excursions, less extreme events where the dipole axis crosses the equator and returns to its original polarity, without a full reversal. The Laschamp event, occurring approximately 41,000 years ago, is a well-known example.

How do we know all this? Scientists use paleomagnetism, studying the magnetic signatures locked into ancient rocks. As molten lava cools and solidifies, or as sediment particles settle, they record the direction and intensity of the Earth's magnetic field at that time. By analyzing these "fossil magnets," researchers can reconstruct the field's history, providing data for dating rocks (a technique called magnetostratigraphy) and even tracking the movement of continents and ocean floors over geological time. The earliest evidence suggests our planet has had a magnetic field for at least 3,700 million years.

The Invisible Shield: Significance for Life and Technology

The Earth's magnetic field isn't just a scientific curiosity; it's a fundamental prerequisite for life as we know it. Its most significant role is in creating the magnetosphere, an immense bubble that extends tens of thousands of kilometers into space.

Defending Against Cosmic Threats

The magnetosphere acts as our planet's primary defense against two relentless threats from space:

- The Solar Wind: This is a continuous stream of high-energy charged particles (plasma) constantly emanating from the Sun. Without the magnetosphere, the solar wind would directly impact our atmosphere, gradually stripping away its lighter components. This wouldn't just mean less air to breathe; it would lead to the loss of our upper atmosphere, including the vital ozone layer that shields us from harmful ultraviolet (UV) radiation. Mars, with its vastly weaker magnetic field, is a stark example of a planet whose atmosphere has been largely eroded by the solar wind.

- Cosmic Rays: These are extremely high-energy particles originating from outside our solar system, often from supernovae. They can damage DNA, disrupt electronics, and pose a severe threat to astronauts. The magnetosphere deflects a significant portion of these rays, further safeguarding life on Earth.

Anatomy of the Magnetosphere

The magnetosphere is a complex structure:

- Magnetopause: This is the outermost boundary, where the dynamic pressure of the solar wind is balanced by the Earth's magnetic pressure. It's asymmetric: on the sunward side, it's compressed to about 10 Earth radii, while on the night side, it stretches out into a long "magnetotail" extending over 200 Earth radii.

- Plasmasphere: An inner region of the magnetosphere composed of cold plasma, extending a few Earth radii from the surface.

- Van Allen Radiation Belts: Two concentric, donut-shaped regions (inner at 1–2 Earth radii, outer at 4–7 Earth radii) that trap high-energy charged particles, mostly protons and electrons, preventing them from reaching the Earth's surface. These belts are crucial for absorbing much of the solar wind's most energetic particles.

Geomagnetic Storms: When the Shield Flickers

While generally protective, the magnetosphere isn't impenetrable. Short-term variations in the field are often caused by currents in the ionosphere and magnetosphere, sometimes amplified during geomagnetic storms. These powerful disturbances are typically triggered by intense bursts of solar activity, primarily coronal mass ejections (CMEs)—massive expulsions of plasma and magnetic field from the Sun.

When a CME slams into Earth's magnetosphere, it can compress, distort, and supercharge the field, leading to dramatic effects:

- Auroras: The most visible manifestation, as charged particles interact with atmospheric gases, creating stunning light displays (Aurora Borealis in the North, Aurora Australis in the South).

- Satellite Disruption: Satellites can be damaged by increased radiation, leading to communication outages, navigation errors, and even total system failures.

- Communication Networks: Radio signals, particularly high-frequency ones, can be disrupted.

- Power Grids: Geomagnetic storms can induce strong currents in long conductors (like power lines), causing transformers to overheat and potentially leading to widespread blackouts, as seen during the infamous Carrington Event in 1859 and the Halloween storm of 2003.

Scientists use the K-index to measure the short-term instability of the magnetic field, providing a real-time indicator of geomagnetic activity and potential storm impacts.

Guiding Our Way: Human and Biological Uses

The significance of Earth's magnetic field isn't just about cosmic protection; it's deeply woven into human history and the natural world.

A Beacon for Humanity: Navigation

For centuries, humanity has harnessed the Earth's magnetic field for exploration and navigation. The invention of the compass between the 11th and 12th centuries AD revolutionized seafaring and overland travel, allowing explorers to reliably determine direction even without celestial bodies. Even in the age of GPS, understanding magnetic declination remains critical for precise navigation, especially in remote areas where satellite signals might be unavailable.

Nature's GPS: Magnetoreception

It's not just humans who've learned to use the Earth's magnetic field. Many organisms possess a remarkable ability called magnetoreception, allowing them to sense and use the field for orientation and long-distance migration.

- Bacteria: Certain bacteria contain tiny magnetic crystals that align with the field, helping them navigate towards nutrient-rich environments.

- Insects: Monarch butterflies use the magnetic field to guide their epic migrations.

- Birds: Pigeons and many migratory bird species rely on an internal "magnetic compass" for their seasonal journeys.

- Marine Animals: Sea turtles, salmon, and whales use the magnetic field to navigate vast ocean expanses, finding their way to breeding grounds or feeding areas.

The mechanisms of magnetoreception are still being actively researched, but it's clear that even weak electromagnetic fields from human-made sources can sometimes disrupt this delicate biological compass, highlighting the subtle yet profound influence of Earth's magnetic field on life.

Keeping Watch: Monitoring and Modeling Our Dynamic Field

Given its critical importance, continuous monitoring and sophisticated modeling of Earth's magnetic field are essential. This isn't just for scientific understanding; it has direct practical implications for our increasingly technology-dependent world.

The Science of Prediction: Global Models

Scientists develop and regularly update global models to accurately represent the Earth's magnetic field. Two of the most prominent are:

- International Geomagnetic Reference Field (IGRF): This is a standard mathematical model of the Earth's main magnetic field, updated every five years by international collaboration. It's crucial for everything from satellite operations to geological surveys.

- World Magnetic Model (WMM): Developed by the US National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency and the UK Defence Geographic Centre, the WMM is the standard navigation model used by NATO and is embedded in countless navigation systems, including those on your smartphone. It's updated every five years to account for the magnetic field's continuous drift.

These models rely on an enormous amount of data collected from various sources: - Satellites: Missions like Magsat, Ørsted, CHAMP, SAC-C, and most recently, ESA’s Swarm constellation, provide high-resolution data from space, capturing the field's intricate dynamics from above.

- Ground Observatories: A global network of observatories constantly measures the magnetic field at fixed locations, providing crucial long-term data for tracking secular variation and sudden changes.

More detailed models, such as the Enhanced Magnetic Model (EMM), go even further, resolving smaller-scale magnetic anomalies down to about 56 kilometers (35 miles). These are important for specific applications like mineral exploration or submarine navigation.

Peering into the Past: Historical Data

Our understanding of the magnetic field isn't limited to modern measurements. Scientists have reconstructed historical data reaching back centuries (e.g., the GUFM1 model back to 1590) and even tens of thousands of years through paleomagnetic research (back to 10,000 BCE). This long-term perspective is vital for understanding the field's natural variability, including its weakening trends and reversal patterns, giving us context for current changes.

The Future of Monitoring: A Collaborative Effort

Ongoing monitoring through advanced satellite missions like ESA’s Swarm is more crucial than ever. These missions allow scientists to:

- Improve Magnetic Field Models: Enhance the accuracy of models used for navigation and scientific research.

- Enhance Predictions of Geomagnetic Storms: Better forecasts mean better preparation for potential disruptions to technology.

- Research Field Weakening and Pole Drifting: Gain a deeper understanding of these phenomena and their potential long-term impacts.

This collaborative effort among scientists, engineers, and policymakers is vital. By continuously improving our understanding of Earth's magnetic field, we can mitigate risks and ensure that we continue to harness its benefits for habitability, technology, and navigation well into the future. The invisible shield above and below us is a marvel of our planet, and its continued health is paramount to our own.